Recent investigative research has shown that what doctors previously believed about how broken bones heal could be wrong: fibrin, a protein that was thought to play a major role in fracture healing, is actually not required in the process. Rather, the breakdown of this very protein is what’s necessary for proper repair.

Recent investigative research has shown that what doctors previously believed about how broken bones heal could be wrong: fibrin, a protein that was thought to play a major role in fracture healing, is actually not required in the process. Rather, the breakdown of this very protein is what’s necessary for proper repair.

A research team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center recently investigated how fractures heal and the implications for how to promote fracture repair. What they found was that while many of the current protocols are based on using fibrin to promote healing, bone biology does not require fibrin to heal a fracture.

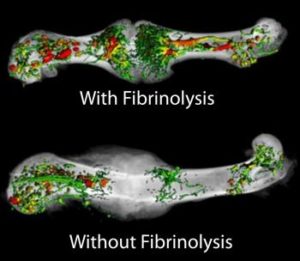

During blood clotting, fibrin forms a mesh-like net of fibers that holds platelets in place to form the clot. When bones break, blood vessels break as well, and the fibrin proteins form these clots to stop the bleeding. What the researchers found is that while fibrin is essential for limiting hemorrhage, its removal – known as fibrinolysis – will actually help healing more so that blood vessels can grow and reconnect, instead of being trapped.

Previously, scientists had assumed that fibrin helps the bone healing process by providing a clotting scaffold to support new bone formation. However, the Vanderbilt team had begun to shift their thinking when imaging techniques showed that reconnection of blood vessels, not blood clots, were important for bone fracture healing. When blood vessels grow following a bone fracture, they extend and reconnect at the ends of the bone’s break, leading to new bone formation. The team then adapted their research based on the thought that conditions in favor of clotting may actually impair fracture healing, and if fibrin is not removed, it could get in the way.

Using mice, the team showed that bone repair was normal in the mice that were missing fibrinogen (the inactive form of fibrin). However, they also found that if mice are missing that factor that helps clear fibrin out of the way, bone healing was impaired due to the blood vessels not being able to attach well to the fracture ends to form new bones.

The researchers are also using the study to help bring more clarity to other factors that could impair bone healing. For instance, conditions such as smoking, obesity, diabetes, and even aging are known to impair fracture repair, but they could now be associated specifically with the inability to clear fibrin effectively due to higher likelihood of blood clots. Also, the study suggests that the reason children’s bone fractures heal more quickly is because their fibrinogen levels are half of those of adults – they don’t have enough fibrin to begin with to impair the healing process.

Have you ever experienced a bone fracture? Tell us the story of your healing process on our Facebook page.